September 1st 2025•

Blog

David Cracknell Starts British Woodland Substack

David Cracknell, renowned piano player and former Sunday Times political editor, has started a substack, Stump Speech @djcracknell, kicking off with a piece musing on the mostly felled Toby Carvery Oak, a 500+ year old Common Oak in North London, and the implications of people’s reactions.

His debut post rightly points out the difference between a natural or a well-managed forest, and a Sitka Spruce forestry plantation where you’d be lucky to see a bird or animal. He is on the money when he says that the best forests for wildlife are managed by humans with a cycle of coppicing, pruning, felling, and mixed species replanting. This skilful human activity prevents the formation of a solid canopy that shades out the forest floor, allowing many more species to thrive, and prolongs the life of the grand old trees that aren’t being felled.

But his post also begs a big question.

David states:

“There is a failure – not just among the public, but policymakers, commentators, and even some arborists – to grasp a few basic facts about how trees live, die, and regenerate. Until we address this, our woodland policy will continue to falter, no matter how many trees we plant.”

Which is fair enough, to an extent. Many years ago, I was coppicing some neglected hazels in Kent, when someone driving past got to the end of the road, turned around, parked nearby, got out and began shouting at us for “destroying trees”. Naturally, I explained that these were invasive Canadian killer hazels, and I was on a mission from John Major to save England; that was the end of the matter.

However, one could reasonably reply to David, “is lack of knowledge among policymakers actually the reason for the state of Britain’s forests? Surely it is plausible that the people in charge are fully aware of how trees live, die, and regenerate, but operate according to other concerns, such as making money and keeping their boss happy.”

A cynical person might go one further: does David’s case really go against these policymakers, or is it making rather poor excuses for them, pleading ignorance on their behalf about their own careers?

I don’t know, but it’s pretty central to his argument. If the problems with managing Britain’s forests are not the result of poor education among policymakers, then all the education in the world won’t fix a woodland sausage. David indicates this when he says,

“Despite the rhetoric, British forestry policy still leans heavily toward plantation silviculture and imported conifers. Natural regeneration – our woods’ own way of healing – gets scant support. Vague terms like “multi-purpose forestry” and “low-impact silviculture” pepper strategy papers, but this rhetoric lacks the practical guidance foresters need.”

I leave it in your hands to decide whether it’s physically possible to be both woefully uneducated on doing the right thing with forests, and to produce clever rhetoric for public consumption that creates the illusion of doing the right thing while really doing the profitable thing.

David’s post ends on a note that sounds like it’s pointing a finger at you and me, Dear Reader, rather than the policymakers and industry leaders who run the show.

“Britain’s love of trees is real, but it needs to grow up. We need an ecological maturity that sees a felled tree not just as loss, but as renewal.”

What do you mean ‘we,’ Kemosabe?

The “ecological maturity” of the average person has nothing to do with Britain’s forestry policy. We have no say over any forests, unless we own one.

And that is the note I want to end on. We deliver plants to thousand of people, many of whom are thinking, and planting, along these lines:

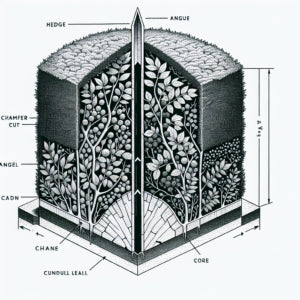

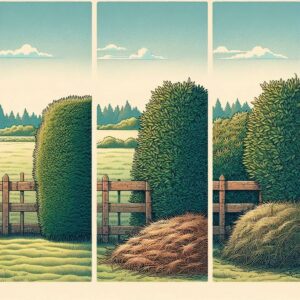

Where there is room for a hedge, there is room for a slice of forest: native hedges are perfect, but any mixed species hedge is better for nature than a single species.

In most fields there are a few square metres in the worst corner that could be spared for a mini forest, perhaps inspired by Miyawaki Method high density planting, or one huge weeping willow whomping in that boggy spot at the bottom.

Forest owners want to enhance the usefulness, beauty, and financial value of the woods, as well as its wildlife capacity. Felling trees creates essential dead wood habitat on the ground for beetles, firewood or timber, and opens space to plant ten times more trees.

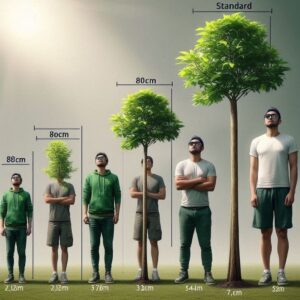

When planting any forest, you will use bareroot tree “whips”, meaning young, usually unbranched trees under 1 metre tall, or small, cell grown conifers that have a plug of soil on their roots.

The bareroot planting season is in Winter, roughly November-March. You can order bareroot sapling trees suitable for any forestry project (or hedge – it’s almost the same thing, just bushier), for the 2025/26 Winter planting season now, and pay nothing until right before they are delivered.

Read More